Buckle Up, We’re Going on a Tangent

Cat at the wheel of a car wants you to get in

Two weeks ago on LinkedIn, I said that I was writing a blog uniting the unlikely duo of William Gibson and Winnie the Pooh. I don’t know if this will work, for as Pooh says:

"when you are a Bear of Very Little Brain, and you Think of Things, you find sometimes that a Thing which seemed very Thingish inside you is quite different when it gets out into the open and has other people looking at it."

—The House at Pooh Corner, A.A. Milne

I’m no more an expert on AI than I am a scholar (or even deep reader) of science fiction. I’ve read enough to know that most of it goes over my head while teasing my tongue with a taste I can’t quite name—a mix of delicious and repellant. But I remember reading Neuromancer and Snow Crash in college during a brief fascination with cyberpunk, and earlier this year I picked up Anton Hur’s debut novel Toward Eternity for a host of very different reasons (one of them being that it was glowingly reviewed, another being that Hur translated the English version of Beyond the Story, a history of the first 10 years of K-pop phenomenon BTS).

Toward Eternity uses gorgeous prose, startling imagery, and keen literary self-awareness to explore the world of an AI “translated” (for my lack of a better term and in a cringe fangirl nod to Hur) into human form. It sensitively and imaginatively invites us to reflect on the scope of human experience through the experiences of this, and other, synthetic beings. It offers no easy answers beyond—ultimately—love.

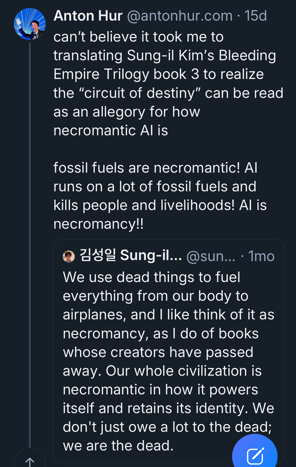

Following the author on Bluesky, I was intrigued by a skeet he wrote in response to another Korean author’s post, earlier this month:

screen shot of anton hur quote skeet of sung-il kim

Sung-il Kim: “We use dead things to fuel everything from our body to airplanes, and I think of it as necromancy, as I do of books whose creators have passed away. Our whole civilization is necromantic in how it powers itself and retains its identity. We don’t just owe a lot to the dead; we are the dead.”

Hur: “I can’t believe it took me to translating Sung-il Kim’s Bleeding Empire Trilogy book 3 to realize the ‘circuit of destiny’ can be read as an allegory for how necromantic AI is

fossil fuels kill people and livelihoods! AI is necromancy!!”

I’d been ruminating on AI as instrument and accomplice to death-dealing in the DOGE-enabled defunding of USAID and big tech’s servicing of Israel’s genocidal campaign in Palestine, which put me in mind of the necromongers in The Chronicles of Riddick. To hear Hur and Kim use the term “necromancy” struck a chord.

As a witch, I respect traditions that honor and even commune with our ancestors, but paying respect to the dead is one thing—worshipping death quite another. I offered my own response on the Bluesky thread:

“This is kind of blowing my mind… AI and necromancy and worship of the dead and is this a perversion of ancestral wisdom and for a Bear of Very Little Brain it’s daunting and also tempting to my tummy….”

Considering the nihilism apparent in the white nationalist broligarchy’s policies, it’s not a surprise that some of these industry leaders subscribe to (or at least flirt with) ideas of technoimmortality (Kurzweil) or transhumanism-into-posthumanism (William Gibson’s Necromancer narrative). I can’t pick a part to excerpt, so for an introduction to Kurzweil that is 100% fire, check out “Ray Kurzweil, Evangelist of Techno-Immortality,” by journalist and Rachel Carson Environment Book Award winner Andrew Nikiforuk. One analysis of Neuromancer (offered by a blogger identifying only as AgriGen) that may be useful is linked here, and excerpted below.

“Through a transition from transhumanity into posthumanity and technological singularity that encompasses the whole novel, Gibson argues that the merging of human and technology should not be seen in a negative light; it should be accepted as an inevitability. Furthermore, Gibson uses linguistic techniques to muddle the distinction between human and technology and further persuade us to drop the negative connotations associated with body and mind invasion.”

Welcoming “the singularity,” these (mostly) male technofascists fancy themselves the New Gods. In their hubris they are anti-nature, in their arrogance ahistorical. Purporting to offer technology for all, they are all about preserving “me” over “we.” Because it is about death for everyone but themselves—they don’t, in fact, welcome death but seek to DOGE (excuse me) dodge it. It is basic, primal FEAR gripping them by their balls. Not Death Eaters but death cheaters.

AI is used to hasten death today and seems to be dreamed of as a pathway in the future to a rejection of human life itself. A white supremacist perversion of various global cultures’ veneration of the dead is a worship of technology, and a world in which we don’t honor our ancestors but convince ourselves that we had none. When we have no past, what does this mean for our ability to imagine a future?

AI is death because it is not sustainable energetically—there simply aren’t the resources to grow it the way that its appetite demands. We’re feeding it with drinking water when people don’t have it and we’re sacrificing communities to deadly pollution. There’s no algorithm that makes that okay.

In this, its current form, AI can’t show us anything new. I don’t even care if it, like Philip K. Dick’s fictional androids, dreams of electric sheep. Only we can dream our way forward.

Tangent to a Tangent

If fossil fuels are our dead, we’re not honoring them by guzzling their oil,

Commodifying them as nonrenewables to burn on no altar but that of capitalism,

Hastening our own demise. It is sacrilege.

In the coming months, celebrations like Halloween, Dia de Muertos, and Samhain will honor those who have passed and give space to those who wish to reflect on transition and blurred boundaries between life and death. They acknowledge that boundaries do exist and approach those boundaries with intention and ritual and care. We do not operate like AI, stealing knowledge from those who have gone before—we offer gifts.